A project based on a similar well-established program in the United States focused on keeping older adults in their homes longer is trying to get its feet off the ground in Burlington.

The Burlington incarnation launched in January of 2020 and provides comprehensive care for older adults as an alternative to long-term care facilities. It currently has 140 Halton Community Housing units in Wellington Terrace at 410 John Street.

City councillor Paul Sharman helped spearhead the Burlington program.

Sharman’s quest to bring better care to seniors began when his mother had to be moved to a long-term care (LTC) facility from a retirement home after apparently “assaulting” another community member while in distress. His mother was deemed violent even though she was frail.

An Earth Day event where the lights were turned off for an hour spooked Sharman’s mother, who was suffering from dementia, resulting in her pushing away the other community member when they approached her.

This unnamed LTC facility also had locked wards for residents who were considered “violent,” where younger residents with mental health and other issues were also located and would allegedly assault other residents.

After much advocacy by Sharman’s sister, their mother was eventually moved out of the locked ward to one mostly occupied by residents who had suffered from strokes. Eventually, she developed pneumonia, was unable to swallow antibiotics, and was then moved to a hospital. By then, her options were limited and she passed away in early 2015.

“Long-term care is necessary but insufficient,” said Sharman. Sharman believes that things could have been better for his mother had there been more support services available in the community. His mother inspired him to look for ways to develop support groups for older adults so they could stay in their homes as long as possible and therefore have a better quality of life.

He and others got as far as setting up a non-profit organization that practiced in condo towers and other places of congregate living.

The local Community Care Access Centre (CCAC) was very engaged and interested and wanted to give them access to their services kit, meaning they would organize services for those people who needed help at home.

Healthcare system restructuring meant that CCACs were disbanded, though. While those services still existed operating under a different name, the future became unclear without the CCAC, and the program was suspended.

But while in Washington at a conference, Sharman was invited to visit a charitable organization in Detroit.

So he and Rick Goldring, Burlington mayor at the time, went down and visited Presbyterian Villages and United Methodist Retirement Communities, thousands of income-geared condo-style homes that were rented to people on limited incomes.

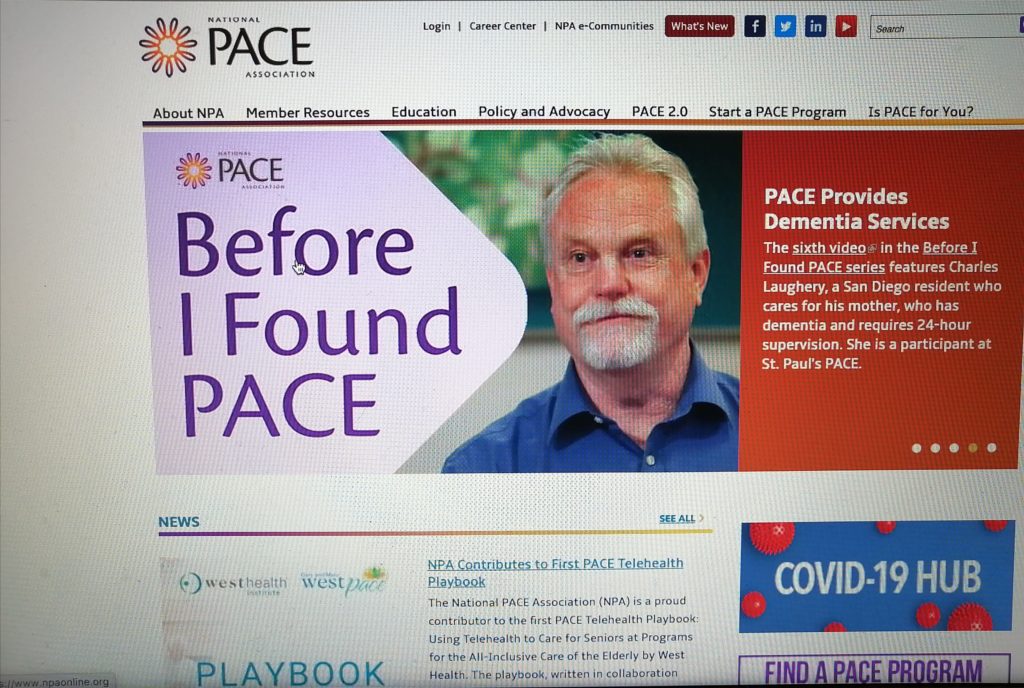

And on the ground floor of all of this was a program called PACE. Other communities were served by standalone PACE centres.

The American-based PACE (Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly) currently runs 142 programs in 272 centres across 30 states.

Sharman and Goldring were shown around and introduced to board members, and the whole way back from Detroit, they were discussing how Presbyterian and United Methodist villages were able to pull together so many housing units with limited resources and what exactly made it work.

To help, Dr. Jennifer Mendez, a Toronto-based professor who taught geriatric care to medical students at Wayne State University in Detroit and an advisor to PACE in Detroit, was brought in to provide support for the Burlington project.

Mendez, now retired, has been involved with the American iteration for more than 25 years, first starting in Milwaukee.

Her initial role was as a physician’s assistant, but after she moved to Detroit, her role expanded to helping medical students get involved with the program in ways such as delivering a falls prevention program and recording biographies, where they would find out about each persons’ past, including their early life and their interests.

“We have physicians in this program, you’ve got occupational therapists, physical therapists, you’ve got music therapists, you’ve got nurses, you’ve got nurse’s aides, you’ve got social workers, you’ve got a podiatrist, you’ve got a hairdresser,” said Mendez. “You’ve got everybody there, but you only use them as you need them.”

Mendez says collaboration between all of the service providers is essential for the success of the program.

Sharman’s team then presented the idea to a special meeting of 80 Burlington community leaders, including Eric Vandewall, President and CEO of Joseph Brant Hospital, and Dr. Michael Shih of Emshih Developments, who specializes in the development of medical buildings and retirement homes.

When the presentation was over, Sharman asked the assembled leaders if anyone could think of any reason not to pursue this program going forward. The room was silent. People then asked what would be done next.

This resulted in Sharman and Goldring setting up committees to discuss how PACE might be established in Burlington. Vandewall and Shih were brought on to the volunteer committee and after about eight or nine months of talking it through, the program was moved into the Local Health Integration Network (LHIN), as they had all the resources and connections necessary for it to work, coupled with Halton Community Housing, which owns and operates large housing properties for older adults.

Residents over 80 years of age make up about 6% of the population in Burlington, with that number estimated to almost double in the next 15 years.

“I think this is the population that requires the most attention,” said Shih. “Social isolation is a problem.”

“Also because of the seniors living much longer now, in terms of care and [their] financial situation, everything needs more attention,” he added.

Unfortunately, just after the pilot program launched last January, PACE couldn’t offer new services or group programs due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the organizations that were already working with residents were able to continue doing so.

The pandemic shed an extremely negative light on long-term care in the province, giving PACE a chance to stand out and continue to grow.

And with the help of vaccines, the program has been back up and running for about six months and has been granted approval from the Burlington Ontario Health Team (OHT), operating out of Joseph Brant Hospital, to scale up and continue its work. Halton Community Housing has also committed $1 million for renovations on the ground floor of Wellington Terrace to better house PACE and its programs.

For more on PACE’s continued growth, including plans for additional Halton Community Housing communities, stay tuned for part two of this series.