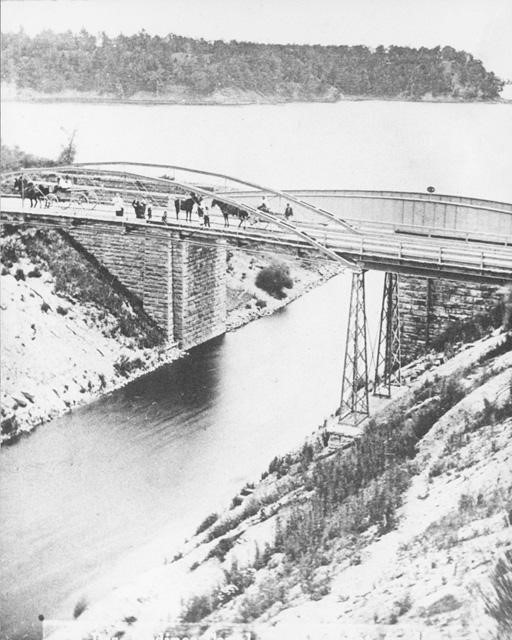

Railroad bridges are intriguing because they carry an extreme load. The engineering that goes into supporting freight trains far exceeds that of engineering to support other means of transportation (except bridges that carry boats — those actually exist!). Let’s look at two of the railroad bridges over the Desjardins Canal — the oldest and the youngest (see Figure 1).

The first railroad bridge over the canal is the eastern-most bridge (harbour side), built in 1853 by the Great Western Railroad Company, carrying two tracks accessing the large rail yard to the east. The latest railroad bridge, built right next to it in 2016, added a third track to improve GO Transit service to Hamilton (see Figure 2).

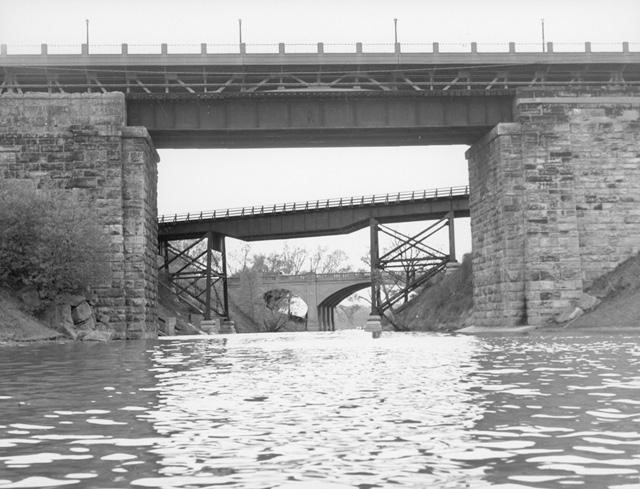

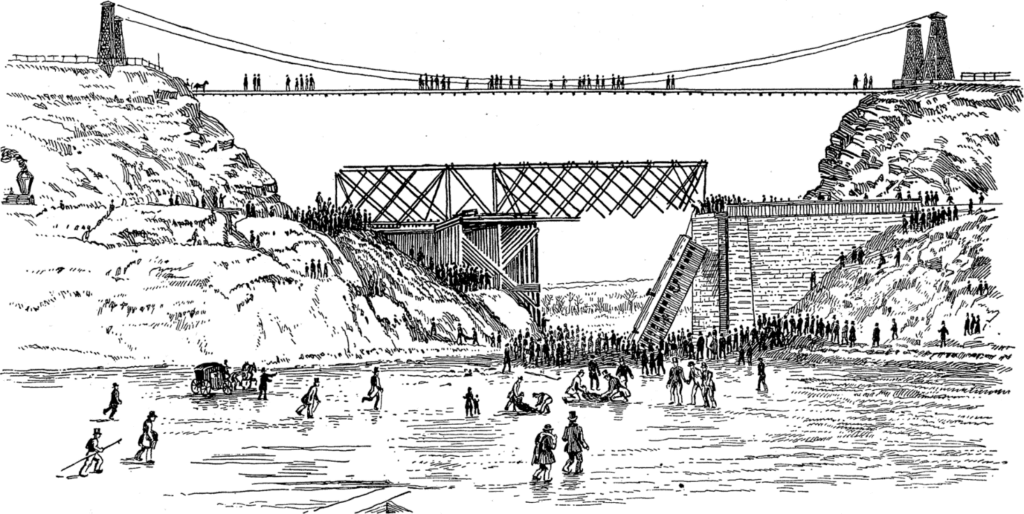

The original bridge on these abutments was a wooden swing bridge allowing tall ships to pass through the canal. It collapsed in 1857 under the derailment of a steam locomotive, leaving fifty-nine people dead — a terrible accident known as the Desjardins Canal Disaster (see Figure 3).

The bridge was replaced right away with a steel plate girder swing bridge on the same original stone abutments. But in 1897, the bridge was replaced AGAIN with a stronger fixed-span steel plate girder bridge, bringing an end to the passage of tall ships (see Figure 4).

The original stone abutments remain in use today supporting the latest (fourth) superstructure built in the 1980s with prestressed concrete box girders. In 2016, a neighbouring bridge was built to carry a third track to the Hamilton CN Rail Freight Depot and the new GO station (see Figure 5).

The main span of the new bridge over the canal is a robust deep-plate girder system made of weathering steel (much more resistant to corrosion), and the back spans connecting the piers to the abutments at the top of the slopes are made of two wide precast deck structures filled with ballast, very common in railroad bridge construction today. The new concrete bridge piers were also made to mimic the stone of the older neighbouring bridge (see Figure 6).

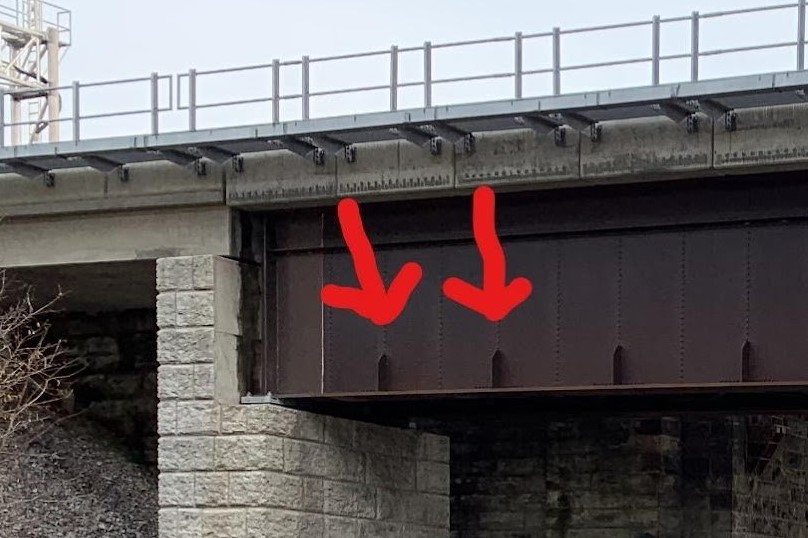

One of the downsides of weathering steel is that it tends to bleed over time onto the concrete piers, leaving long, rust-coloured streaks produced during rainfalls (more so than regular steel). For this reason, the ends of the girders are often painted to reduce or eliminate staining (see Figure 7).

The deeper the girder is, the higher its capacity to carry loads. Its web (the tall vertical plate between the flanges), however, also becomes more flimsy, subject to buckling without additional supports and stiffeners. This is why there are gusset plates (stiffeners) at the bottom of the web along with a series of cross braces between the girders (see Figure 8).

The two old bridge abutments built in 1853 have supported several different superstructures over the years. Today, the span is made of precast box girders laterally bolted together with four steel rods, making them act as one monolithic structure instead of independent girders (see Figure 9).

There are also steel brackets near the top of the abutments facing the canal, which were probably used for a temporary jacking frame to replace the deck in the 1980s, left in place in the event that the deck needs to be replaced once again (see Figure 10).

It’s always fascinating to see old infrastructure next to new, telling the story of the country’s need for transportation decades ago and how our ancestors delivered on that need. And it becomes a testament to our growth and industriousness as new infrastructure is built to increase capacity over time. When walking by these structures, look at them closely and don’t forget to be impressed. Be safe!

Have you seen an interesting building or piece of infrastructure in or around Burlington that you’d like Eric Chiasson, your personal engineer, to write about?

Send us your suggestions, comments, or questions to articles@local-news.ca and we’ll see what Eric can find out!

Sources:

Structure Magazine. Desjardins Bridge Disaster. Url: https://www.structuremag.org/?p=15353 (accessed Dec. 19, 2021).

Hamilton Public Library. Local History and Archives. Desjardins Canal Disaster. Url: https://lha.hpl.ca/articles/desjardins-canal-disaster (accessed Dec. 19, 2021).

Historic Bridges.org. Desjardins Canal Railway Bridge. Url: https://historicbridges.org/bridges/browser/?bridgebrowser=ontario/desjardinscanalrail/ (accessed Dec. 19, 2021).

The Spectator. March 12, 1957. 59 Die in Desjardins Canal Bridge Railway Disaster. Url: https://www.thespec.com/news/hamilton-region/2016/09/23/march-12-1857-59-die-in-desjardins-canal-bridge-railway-disaster.html (accessed Dec. 19, 2021).

For more info on the Desjardins Canal, read my articles How It Works: The Desjardins Canal, and How It Works: The Desjardins Canal High Level Bridge.

For more information on the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/eric-chiasson-10601082