The most diverse collection of bridges you’ll ever see in one spot are the bridges over the Desjardins Canal in Hamilton. The canal connects the waters from the Cootes Paradise Marsh (managed by the Royal Botanical Gardens) to the Hamilton Harbour. It bisects a thin stretch of land called Burlington Heights (actually in Hamilton) and every transportation entity in the province decided to build a bridge here over the past century. In fact, it looks like they fought for supremacy over the canal — which is kind of what happened!

Today, there are seven bridges spanning the canal, carrying highway traffic, freight trains, pedestrians, city traffic, VIA Rail, and GO trains (see Figure 1).

The most notable bridge over the canal is the iconic 111-metre-long High Level Bridge, built by the Hamilton Bridge Company in 1923, carrying York Blvd. with its beautiful structural steel arch and its four limestone pylons above the roadway at the corners of the bridge (see Figures 2 and 3). The bridge was renamed the Thomas B. McQuesten Bridge in 1988 after the Minister of Highways at the time of construction (though no one calls it that).

This bridge was built as a cantilever deck truss meaning that from each pier (the vertical towers holding up the span), it was built out segmentally towards the canal (the main span), while the weight of the truss behind the pier (the back span) acted as a counterweight, preventing it from falling into the canal (take a good look at Figure 2 again). Developed in the mid-1800s, this construction method significantly advanced bridge construction, allowing for longer spans and safer construction. The High Level Bridge is made of thousands of steel plates rivetted together — evidence of the time in which it was built. Bolts can be found in the structure where retrofits were made, as no one uses rivets for bridge construction anymore. With the entire roadway on top of the structure, and using its arch shape, the whole structure is acting in compression. The open lattice construction of the beams gives the structure a lighter, more see-through, elegance.

Looking up under all the bridges crossing this canal is fascinating from an engineering perspective — it’s like a mechanic looking up at the undercarriage of a car, you can see everything you need to know about the bridges (see Figure 4). For example, the railroad bridges at the lower levels have taller girders close together with significant bracing between them and a shorter span between the piers, giving them the ability to carry a much heavier railroad freight load, whereas a regular highway bridge will have shorter girders, wider spacing, less bracing, and usually a longer span.

But how graffiti artists access some of these bridges is beyond me!

The City of Hamilton had planned on setting commemorative statues in each pylon by the roadway welcoming travellers to Hamilton, but never have, leaving the pedestals empty ever since (see Figure 5).

Steel trusses were common in the 1800s and most of the 1900s because they could be easily analyzed in terms of reaction forces in each member of the truss from its own weight (dead load) and the vehicles on top (live load). They could be developed for virtually any configuration, regardless of the span length or height, or of the load it was to carry. A steel column in compression will buckle under small loads, whereas a truss is significantly more stable under any load — compression, tension, torsion, bending. When these physical properties of steel became well-understood, engineers from around the world invented countless types of trusses for different applications.

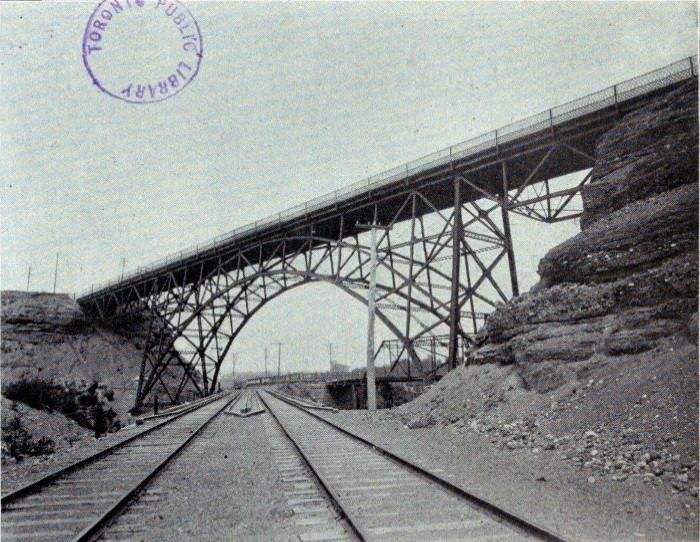

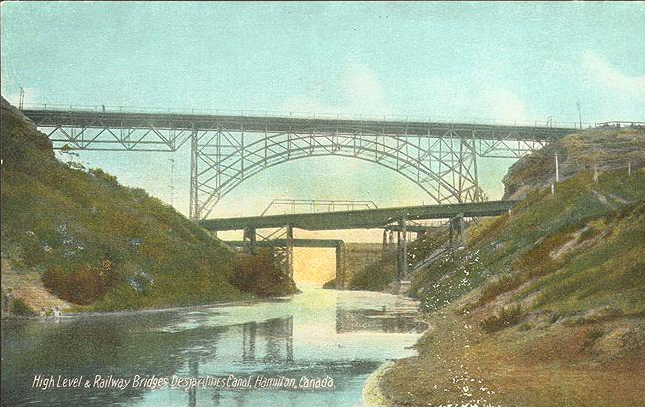

This bridge’s predecessor, built sometime between 1880 to 1899, had a similar look, with a tall structural steel arch spanning over the railroad tracks (see Figures 6 and 7, courtesy of Toronto Public Library).

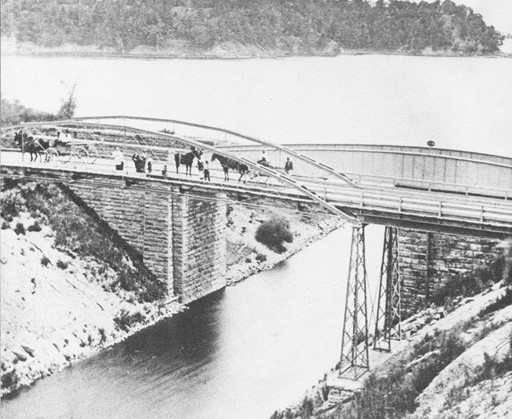

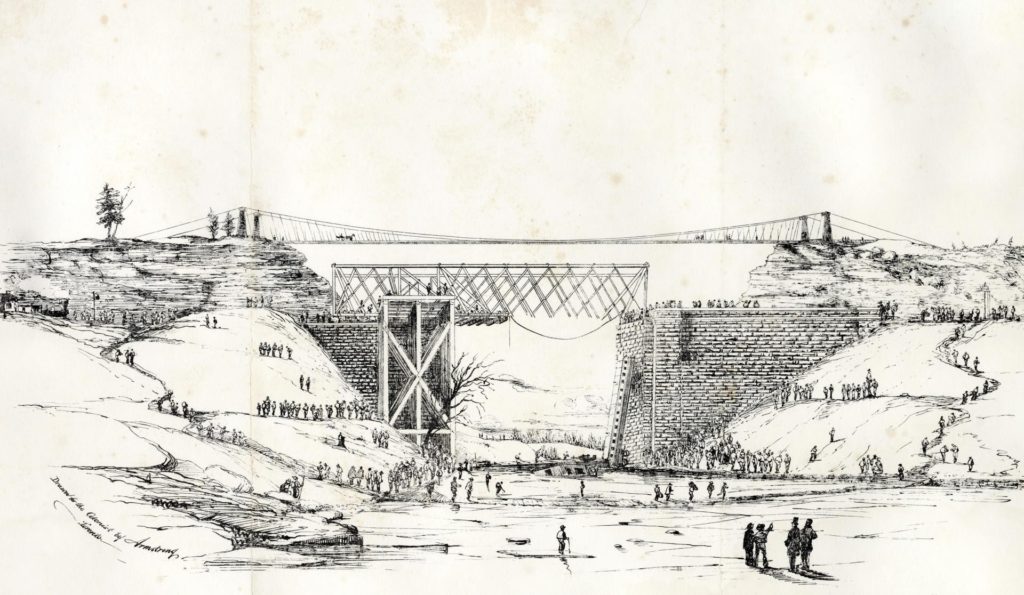

The first two bridges in this exact location were a suspension bridge and an overhead arch structure, as depicted in the renderings in Figures 8 and 9, courtesy of the Hamilton Public Library Archives.

As cities grow, so does their infrastructure. When the Desjardins Canal was opened, it created a chain reaction of bridges being built and demolished for various reasons over the course of the following 150-plus years, making this one of the most interesting places in terms of bridge engineering in both past and present technologies. The current High Level Bridge is a beautiful structure, easily accessible above and below via well-travelled multi-use paths. If you’re a bridge enthusiast, pay it a visit and don’t forget to look up!

Have you seen an interesting building or piece of infrastructure in or around Burlington that you’d like Eric Chiasson, your personal engineer, to write about?

Send us your suggestions, comments, or questions to articles@local-news.ca and we’ll see what Eric can find out!

Sources:

Chiasson, E. 2021. How Things Work: The Desjardins Canal – Marine Shipping Channel Retired. Local-news.ca. Url: https://local-news.ca/2021/12/01/how-things-work-the-desjardins-canal-marine-shipping-channel-retired/ (accessed Dec. 4, 2021).

Canadian Transport Sourcebook. High Level Bridge. Url: www.transportsourcebook.ca/imagepages/high_level_bridge_hamilton_canada_pc.php (accessed Dec. 4, 2021).

Hamilton Public Library. Local History and Archives. Desjardins Canal Disaster. Url: https://lha.hpl.ca/articles/desjardins-canal-disaster (accessed Dec. 4, 2021).

Historic Bridges.org. Thomas B. McQuesten High Level Bridge. Url: https://historicbridges.org/bridges/browser/?bridgebrowser=ontario/yorkboulevardbridge/ (accessed Dec. 4, 2021).

For more information on the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/eric-chiasson-10601082