Tracy L. Cain presents her unique family history to audiences of all ages through a mix of song and storytelling, all to shed light on Black Canadian history — until, ultimately, it is a regular part of the telling and teaching of Canadian history.

Cain, you see, is a bit of a unicorn: she is part of the fifth generation of Black Canadians in her family —on both her maternal and paternal sides.

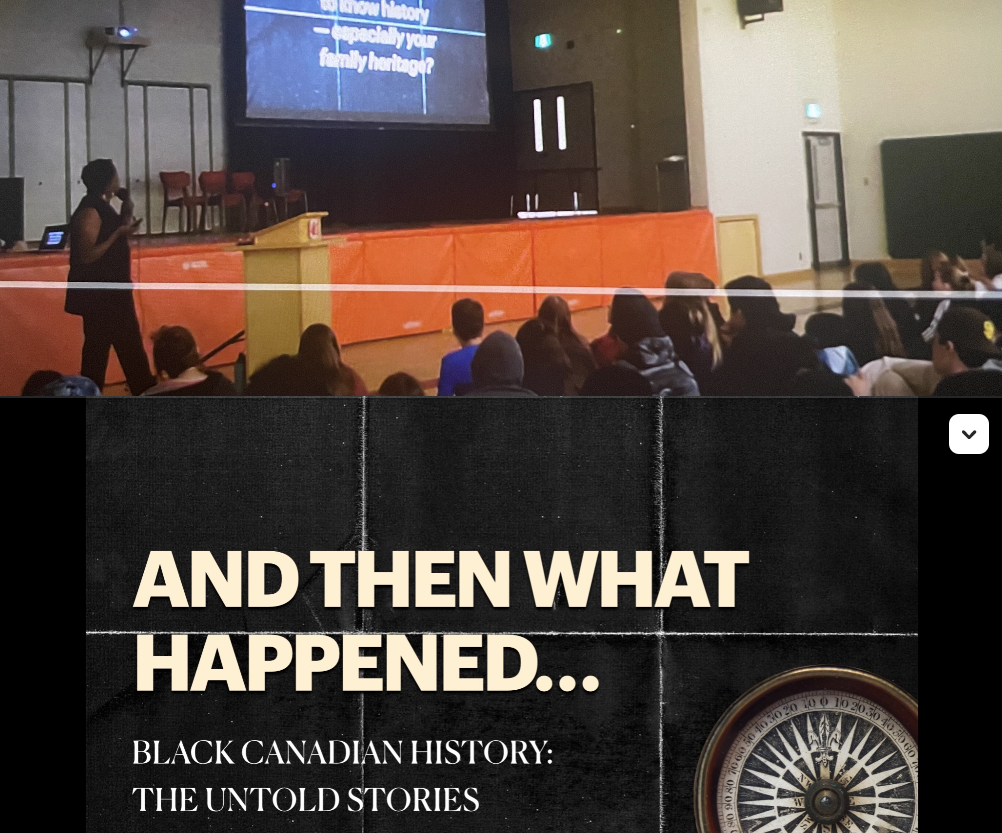

ONE Burlington is presenting Cain’s one-woman performance “And Then What Happened: Untold Stories of the Underground Railroad with Songs and Stories by Tracy Cain” on Sat., Feb. 17 in celebration of Black History Month. The free tickets were snapped up weeks before the event; Burlington residents clearly want to hear what happened.

Cain offers presentations year-round, though, not just during Black History Month, at schools, and for other interested groups. Students in grades 7 to 9 are her sweet spot, though, and Cain works to engage the students with her material. “Students tend to sit open-mouthed the whole time they watch,” she says, with teachers saying “I’ve never seen them sit still for so long!”

For Black students in particular, Cain notes, “There’s a disconnect in their identity from not knowing much about our own history.” Her presentations offer a new connection to their history, perhaps a re-connection.

“It’s very important,” says Cain. “Without knowing where you came from, you don’t know where you’re going.

While Cain has always known where she comes from, in that she knew she was a fifth-generation Black Canadian with ancestors who escaped enslavement in the United States via the Underground Railroad, her deep dive into the stories of her ancestors really only began in 2019. And then when the pandemic hit, Cain’s husband, Robbert Kramer, an amateur genealogist, said to her, “Your family has a lot of history, you should be telling people about it!”

Since then, Cain describes, “It’s a rabbit hole that keeps getting deeper and deeper.”

There’s the DNA angle: Cain took one of the home DNA kits in 2019, then asked her sister and parents to do the same. They are still finding more and more relatives this way.

Then, it’s asking the right questions of the right people — “And a lot of luck,” Cain notes — to find out more about her ancestors and their stories.

“There’s so much to dig through. I have a very large family. The joke is, I don’t have a family tree, I have a forest!” Cain says, laughing.

She has now been presenting the stories of some of her ancestors in public for around two and a half years.

As for the musical aspect of her presentations, that came naturally to Cain, who has long been a singer and actress alongside her full-time job in a credit union.

In fact, Cain has been singing on stage since she was 3 years old. Her immediate family used to tour as the Winston Johnston Singers, singing gospel songs. Here, she follows in her father’s footsteps: her father, alongside 11 of his siblings, toured as the Royal Canadian Harmony Singers. He, too, was on stage at 3 years of age. Her mother also sang throughout Ontario, and her sister, Karen Burke, is the director of the Toronto Mass Choir.

“Music, in our family, is like breathing,” Cain explains.

No surprise, then, that music features in Cain’s presentations.

It’s “a lot of music from the past — I bring the music from Negro spirituals…and decode them,” Cain explains. It is not uncommon to hear from adult audience members post-show that they knew the songs she sang, but had no idea that they were written by enslaved people.

At her school presentations, Cain sings with the students before decoding the meanings behind the lyrics. After that, there’s Q&A time. The teachers, Cain says, usually have to cut off the questions because of the sheer number of them posed by students. “The information has been buried for so long, and it’s not taught in schools.”

As for the storytelling aspect of her performances, Cain talks about four of her ancestors: Josephus Malott, Andrew Lucas, Allen Cooper, and the Right Reverend Samuel Richard Drake.

The first three men were enslaved in the United States, and each had a unique journey to freedom. Malott purchased his freedom; Lucas was a runaway, who fled to Canada to find freedom; and Cooper was willed to his freedom.

Malott was Cain’s great-great-great-grandfather, who, after purchasing his freedom, settled in the Queen’s Bush area in the late 1820s with other freedom seekers, near what is now Wallenstein, and west of what is now Elmira.

These early Black settlers put in much hard labour to clear the land and build homesteads for themselves. Malott himself cleared over 20 acres.

“For them to have to go into that wilderness, with an axe, or a knife, to literally cut down what had to be cut down…it’s incredible,” says Cain of the Queen’s Bush settlers. “When you think of Canadian pioneers, you think Laura Ingalls Wilder — but no one knows they looked like me…including me!” Learning about the accomplishments and resilience of Malott and the other settlers has been eye-opening for Cain.

Queen’s Bush turned into a thriving area, with homes, a school, and a church, thanks to the efforts of its Black settlers.

By 1840, it was the largest Black population in Canada, says Cain, with around 1800 people. Then, the federal government came in and surveyed the area.

“The Black people knew they were squatting, they knew it was coming,” says Cain, but that doesn’t make what happened next any easier.

The government agents came in and told the Black settlers to buy the land or to get off of it. Of course, they offered terrible terms of purchase, with prices set high; the government agents were not above harassing the settlers off the land. On top of that, the Black settlers “often couldn’t read or write, they didn’t know what they were signing,” describes Cain.

Malott was never able to purchase any land. His son, however, did purchase some land in Glen Allan later on.

Cain was emotional when describing seeing Allen Cooper’s free papers, which happened after a stroke of luck in connecting with someone whose third- or fourth-great grandfather had been an abolitionist: that person’s ancestor had helped Cooper escape from the U.S. to Canada.

“I was in tears,” Cain says, the first time she saw Cooper’s free papers. “A) because he had to have free papers, and B) because he had to get out of where he was living so that he didn’t have to keep showing his free papers.”

Though Cooper was born free in 1775, he was not officially freed until 1779. This was because the enslaver of Cooper’s mother, who died in 1771 and willed the people he enslaved their freedom, had kept over 500 people enslaved, and his children contested the will: they “needed” to keep these 500-plus people enslaved to work their land. It took eight years for the courts to decide that the will stood, and so Cooper was freed in 1779.

Cooper later settled in North Buxton, which grew to be another thriving Black settlement. Its school was so successful, teaching English, math, geography, and Latin, instead of the trades like most other Black schools, people began bringing their children from as far as Toronto to be educated there. Because of that success, it became the first non-segregated school in Canada.

North Buxton still hosts annual homecoming events for descendants of its Black settlers; Cain performed at last year’s homecoming, as did her sister’s choir, in front of their aunts and cousins.

“It meant a lot to us,” Cain says.

As for Cooper, his headstone at North Buxton says that he lived to be 104 years old.

Then there’s Lucas, another great-great-great grandfather, who, according to his headstone in Brantford, died at the ripe old age of 120 years old. He was born enslaved and had seven children in the U.S. when he left. He married again in Canada and had another 17 children (not a typo: he had a total of 24 children!).

As well as the commonality of being formerly enslaved, Cain’s relatives also had their faith in common. “Freedom, faith, and family, are common bonds,” explains Cain. “Church was a social gathering as well, but the faith part came in and got people coming together, working together, to keep going.”

Cain’s great-grandfather, the Right Reverend Samuel Richard Drake, played a role in his community’s faith and worship — he was the general superintendent of the British Methodist Episcopal (BME) Church for 19 years. His father before him had been a pastor in the same church. Cain notes that BME churches “are all on the spots where freedom seekers went to.”

It goes back to those bonds of freedom, faith, and family: “In these areas, you had to work together as a community to survive and thrive,” Cain says.

In 2021, Cain had the chance to visit Malott’s land, after the Discovery Channel reached out to her to talk about her family’s Underground Railway connections. “I was able to go to the land he cleared, with my sons. By the time we got there, it was quite emotional,” Cain describes. “Not even a year later, it was built over, so no one will ever have access to that land ever again.”

Reflecting on her ancestors’ journeys to freedom, and all they had to endure while in Canada to survive, Cain says, “I often wonder — could I have done that? Their resiliency, their need to make a better life for their families…I want to celebrate what they did in their own communities. I want to learn from the errors they made. I want to learn to work together like they did. How they worked together, as a community — how do we work together to do better?”

Those are the things Cain wants to get people thinking about with her presentations. Sharing Black Canadian history with her audiences gives her lifelong passion for singing and acting a purpose.

“Organically, this has come to fruition, and I’m loving it,” Cain says. And while she loves presenting her ancestors’ stories during Black History Month, she states: “I book throughout the year. 365 [days per year], it’s Canadian history. We’re just lifting the lid off of it.”

Find Cain online on her website, tracylcain.ca, on Instagram (@TracyLCain), and on YouTube here. If your organization or school would like to book Tracy Cain for a presentation, go through her website or click here.