From south of Hwy 5 to Concession Road 5, the Dundas Quarry is Lafarge’s largest in Canada and has been in operation for over 100 years!

If you’ve ever driven on any piece of infrastructure in southern Ontario, then you’ve benefitted from the countless millions of tons of rock mined out of the Dundas Quarry. Operated by Lafarge since 2000, the quarry has been producing about 4 million tons of crushed aggregate every year, supplying infrastructure projects as far as Scarborough to the east, Barrie to the north, and London to the west.

Each rock formation underground has its own characteristics in terms of composition, hardness, abrasiveness, density, and so on. The rock being mined in the Dundas Quarry is from the Rockport, Amabel, and Guelph formations. They are all sedimentary rock, meaning they were formed at the bottom of an ocean (see Figure 2).

The process begins at the cut face or pit face where rock excavation is advancing. Jumbo drills are used to drill deep holes into the rock, which are then filled with an emulsion explosive (and other components) poured into each hole and detonated to separate the rock from its formation (see Figure 3).

The diameter and pattern of the drill holes, the explosives with which they are filled, and the sequence of detonation for the mass of rock is a science on its own. To do this properly and safely takes a lot of experience and a lot of calculations. For a short video on quarry blasting see the link below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBi1NXOnkE4

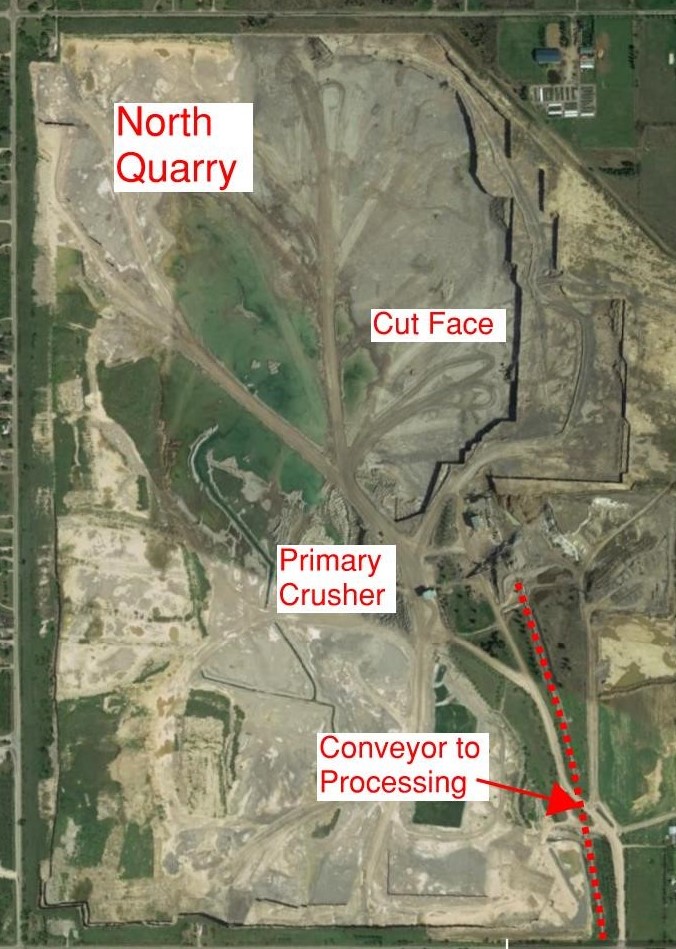

The cut face for the Dundas Quarry is north of Concession Road 4 and is called the North Quarry. South of Concession Road 4 is the South Quarry, which is older and less active. And the southern-most section of the quarry is the oldest, where rock excavation started over 100 years ago and where there is no more rock to be mined (see Figures 4 and 5). This area has become the processing centre where the raw blasted rock (called pit run) is turned into different gravel products, such as road base or aggregate for concrete (see introductory photo).

Once the rock is blasted, it is loaded into trucks and hauled to the primary crusher close by, which breaks down any oversized rocks, preparing this raw material for its 3.5 km journey down the longest conveyor belt I’ve ever seen (the conveyor superhighway) to the processing facility at the other end of the quarry (see Figures 6, 7, and 8).

Blasted rock in its raw form is not very useful from an infrastructure perspective. Engineers who design roads and bridges need the rock to conform to precise specifications. The gradation of the gravel to build roads (road base) needs a specific amount of different size rocks — from golf-ball-size to pea-size to sand. A well-graded gravel will compact better than a clean material where all the rocks in the gravel are the same size (like marbles) — which does not compact well. Manufacturing concrete, on the other hand, requires clean rock to generate concrete with predictable compressive strengths (see Figure 9).

Most of the processing takes place south of Highway 5. The pit run is delivered to the processing facilities via the conveyor belt “superhighway.” From there, it is run through further crushing (which reduces the size of the rock) and screening (which segregates different sizes of rocks, from coarse aggregates to fine sand; see Figure 10).

The quarry has several tunnels on site to eliminate (almost) the need for mining equipment to cross public roads. The conveyor superhighway alone goes through four tunnels. There is also a tunnel under Hwy 5, allowing access to the quarries without interfering with public traffic, making for a much safer environment. A tunnel will soon be built under Concession Road 4 as well, eliminating the public crossing (see Figure 11).

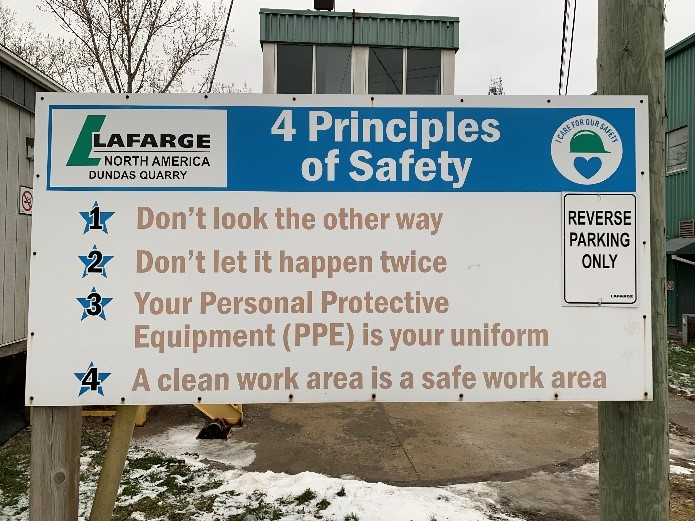

The Dundas Quarry employs almost 100 full-time individuals all year long, and also recruits the help of several subcontractors to support some of their operations. Having been a strong part of the local community for so long, contributing to the construction of southern Ontario, the Dundas Quarry is with us for many decades to come! Don’t look the other way. And be safe.

Fun fact: Johnson Tew Park has an observation point overlooking the Dundas Quarry processing facilities (see introductory photo). Great view! This park was funded by Lafarge and donated to the City of Hamilton.

Special thanks to Peter Sanguineti (Lafarge VP Eastern Canada) for facilitating access to the quarry, and to Jennifer Bolibruch (Dundas Quarry Plant Manager) for taking time out of her busy day to show me the details of how the quarry works.

Have you seen an interesting building or piece of infrastructure in or around Burlington that you’d like Eric Chiasson, your personal engineer, to write about?

Send us your suggestions, comments, or questions to articles@local-news.ca and we’ll see what Eric can find out!

For more information on the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/eric-chiasson-10601082