Monday of this week saw the first Mayor’s Speaker Series event at the Burlington Performing Arts Centre (BPAC), with former City of Toronto Chief Planner and president and CEO of Collecdev Markee Jennifer Keesmaat presenting her vision of how municipalities might move out of the current housing crisis.

Mayor Marianne Meed Ward kicked off the night by outlining the current state of affairs in Burlington, starting with the city’s commitment to maintaining Burlington’s 50/50 urban-rural split by ensuring growth happens within the urban boundaries.

Meed Ward noted that the housing crisis and cost of existing housing means that “the dream of home ownership is slipping away for a whole generation.”

“Housing to income is the biggest disconnect,” she pointed out.

The city is taking steps to ameliorate the housing crisis, including the Pipeline to Permit committee, formed this year; a concierge for “high-impact files”; an allowance of four units as of right on any single lot; the securing of $21 million from the Housing Accelerator fund; and the recent decision to decrease development charges by 15%.

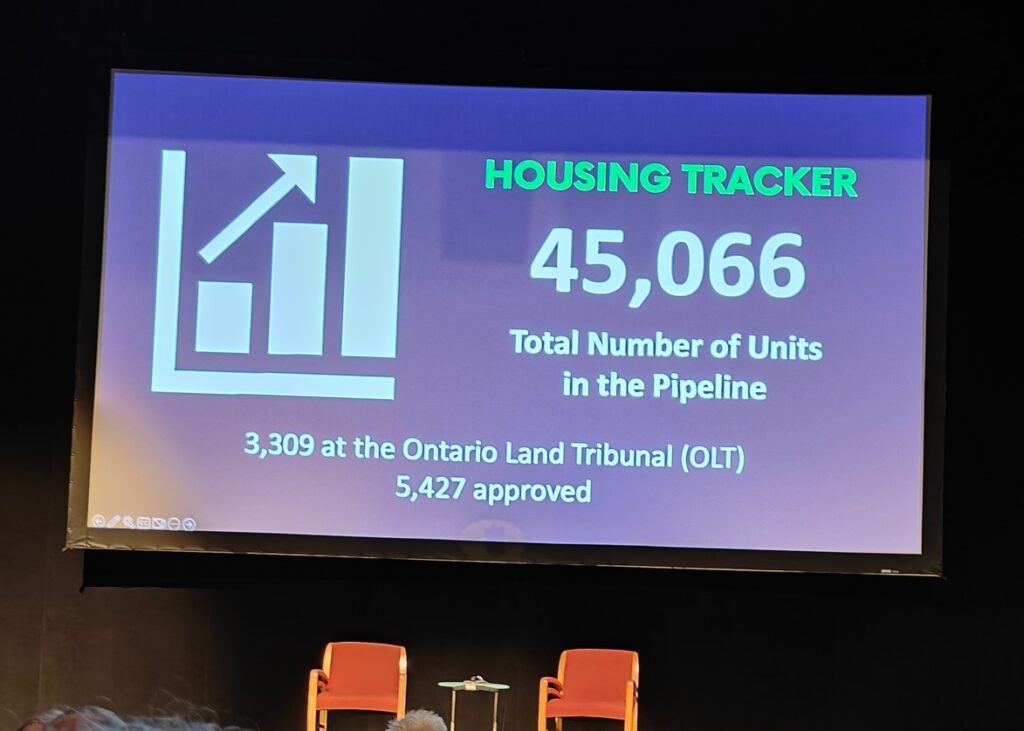

Meed Ward noted that there are some 45,000 units in the development planning pipeline, including those that are in the pre-application stage; the city is working to facilitate the creation of 29,000 units by 2031, the target assigned by the province.

Ward 1 Councillor Kelvin Galbraith stepped up to the podium next, as much development is happening in his ward, driven by the Aldershot Major Transit Station Area (MTSA). MTSAs are strategic growth areas, meant to be designed as complete communities. Burlington has three MTSAs in the works, around each of the GO train stations.

Speaking on the Aldershot MTSA, Galbraith noted that “lots of new units won’t even come with a car [parking] spot,” as the idea is to enable various forms of transportation, including cycling, walking, scooters, and the GO train.

“Everything you need in life will be walkable,” explained Galbraith, in these complete communities around GO stations. “We will see more in-fill communities more than the sprawl we’re used to.”

City Manager Hassaan Basit, after noting that he had “nothing profound to say yet,” given that he’s only been on the job for a month, asserted that his job is to “work in the long-term interests of the city and its residents.” Other municipalities are already looking at Burlington, he said, because of the “innovation and new thinking going on at the city,” from the decrease in development charges to the piloting of AI to speed up development application screening times.

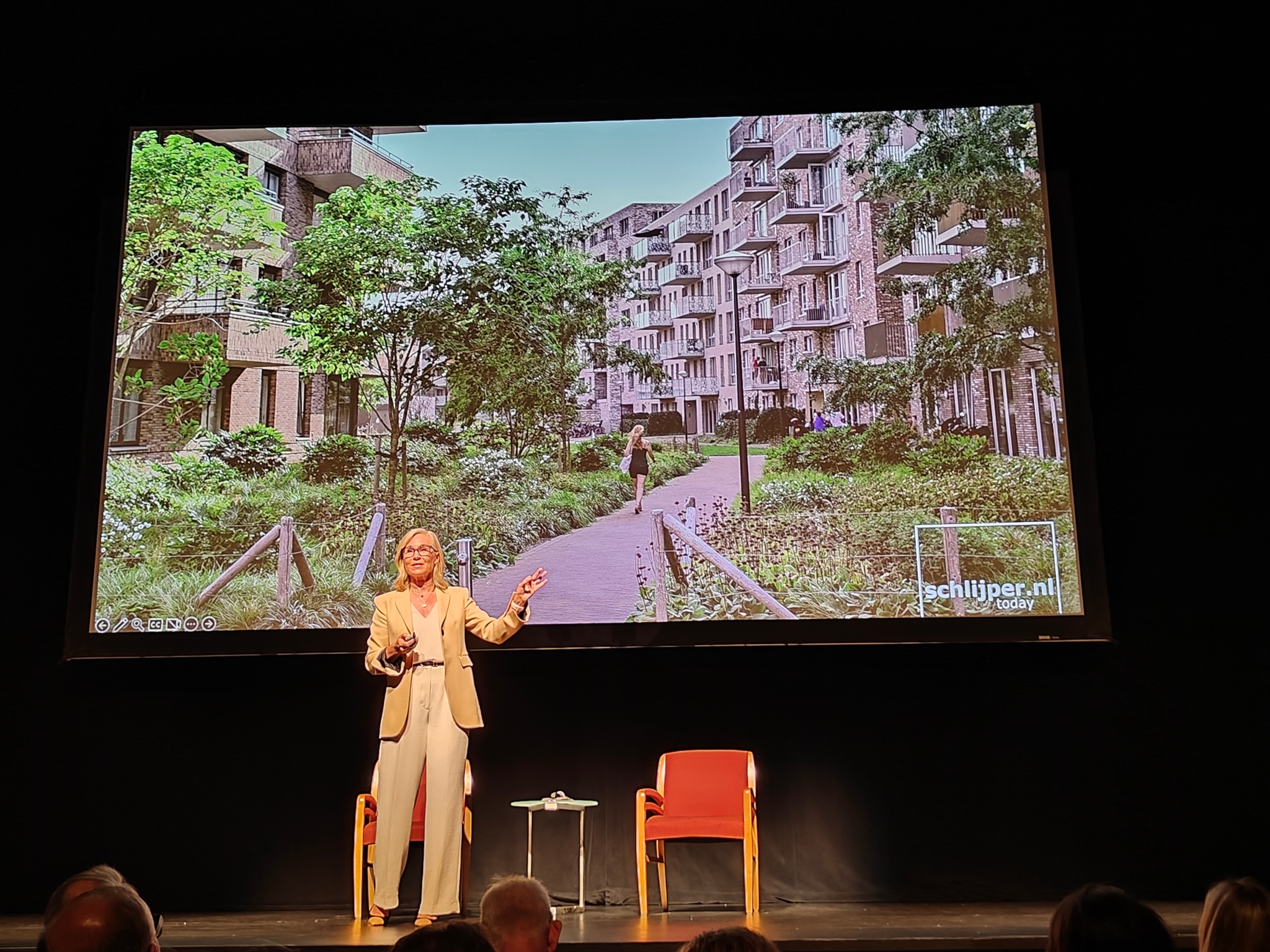

Then came the main event in the form of keynote speaker Jennifer Keesmaat, an engaging and charismatic speaker. Keesmaat presented a vision for what housing could be, communities with housing for everyone, across their lifetimes, appropriately titled “Dream the Dream: Housing for All.”

Keesmaat began by redefining the dream, given that owning a home is becoming increasingly difficult for the average person, particularly people or families relying on only one income. “One hopes that access to clean land, air, and water is an easy consensus point,” she stated.

The dream, then: “Access to stable, safe housing, that is affordable at every stage of a lifetime.”

Next, Keesmaat described the typical way that suburban housing has been developed, compared to what she calls “next generation in-fill neighbourhoods,” encapsulated by Galbraith’s earlier comment about sprawl vs in-fill.

Suburban neighbourhoods have long contained mainly single-family homes, with travel in and out by car. And, Keesmaat noted, traditional suburban neighbourhoods are inherently focused on the private realm and are actually hostile to transit by design.

Next-generation in-fill neighbourhoods, though, contain various housing types, including both rental options and ownership, creating density that can support high-frequency transit as well as promoting walking and cycling, and where the priority is on the public realm (“And public luxury,” Keesmaat emphasized), rather than on private space. This could include recreation centres, greenspace, or any public amenity that encourages people to gather and live out parts of their day in those spaces.

Keesmaat talked the audience through the housing continuum, from market rental ownership to market rental housing, then affordable rental housing, social housing, transitional housing, emergency shelters, and finally, homelessness. She pointed out that the final three categories, though, are not so much categories of housing but rather are outcomes of a broken housing system.

How, then, can we achieve that dream of affordable housing through life for everyone?

Keesmaat’s thesis is that municipalities should focus on affordable rental housing; Helsinki, she said, has actually eliminated homelessness by concentrating on that level of housing, alongside wraparound services that allow people to succeed in remaining in their rental units.

To do that, Keesmaat suggests municipalities look over their existing under-used land, to see where additions can be made, giving the example of a single-storey building that housed service delivery agencies, that is now being built literally on top of to create 500 housing units.

She also suggests examining the existing infrastructure first, to see whether additional infrastructure is needed in order to enable growth and increased density, citing as further reading the Blueprint for More and Better Housing, written by a national taskforce of which Keesmaat was a member. The importance of politicians and developers coming together was also noted but with attention paid to the “middle,” which is where the details reside, which must also be considered.

Keesmaat spoke briefly on projects in other parts of the world that have resulted in complete communities, and innovative solutions, from very low carbon, affordable modular housing units in Denmark, to a 56-acre Toronto site that Keesmaat’s company is redeveloping, which will primarily consist of six- to eight-storey buildings, a few taller buildings, and with that key focus on the public realm: a new community hub, pool, gym, and affordable daycare.

Meed Ward came back onto the stage for a Q&A period with Keesmaat; the audience was invited to submit questions via slido.com, and also to vote on which questions would ultimately be asked of Keesmat.

The questions brought about discussions of a shift that Keesmaat has seen in the attitudes of young people; while their parents might have flocked to the suburbs, Keesmaat is seeing young people who want to live in bigger cities, who want to be able to walk to their destinations, and “don’t mind the trade-off of a smaller [living] space.”

Meed Ward noted that people are often concerned when they hear that a tall building is being planned for their neighbourhood; they are concerned about increases in traffic, in increase in demand for local services, and tend to predict only a negative impact on their quality of life. “How do we help people?” Meed Ward asked.

“I think that response is very rational,” Keesmaat responded, “if there is no transition. There’s a tension, you can’t do it halfway. That’s why we need infrastructure.”

She added that if everyone is already cycling, than you can increase the number of people in a neighbourhood, but if everyone is driving, then increasing the number of people “just adds to traffic.”

What’s needed to avoid those situations, Keesmaat said, is “vision, clarity of what the future will be, and see how all the pieces will fit together.”

And what about people who don’t want change, Keesmaat was asked — how does one deal with that?

“We can change our minds and see our futures differently,” Keesmaat stated. It starts, she said, from talking about shared interests.

For instance, Keesmaat said, “I have yet to meet a Canadian who wants people living in tents in parks. No one wants that.” From that shared interest, she suggested, you can start to get to how things must change.

“It’s about how we live together and how we share resources.”

After all, as Keesmaat said at the end of her formal presentation, focusing on that shared interest to get to that shared dream, “That is something worth working really hard for.”