By Maisha Hasan, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

A citizen science initiative is paving the way to fight against online animal cruelty by way of Prime Earth, a Burlington non-profit.

“Primate Protectors” is Prime Earth’s new project, undertaken to gain information and raise awareness about a kind of primate cruelty that often slides under the radar — taking primates out of their natural environments and into a human habitat, and then treating them as if they were small humans. These primates are then photographed in their t-shirts or diapers and their images are posted online, all in the name of human entertainment.

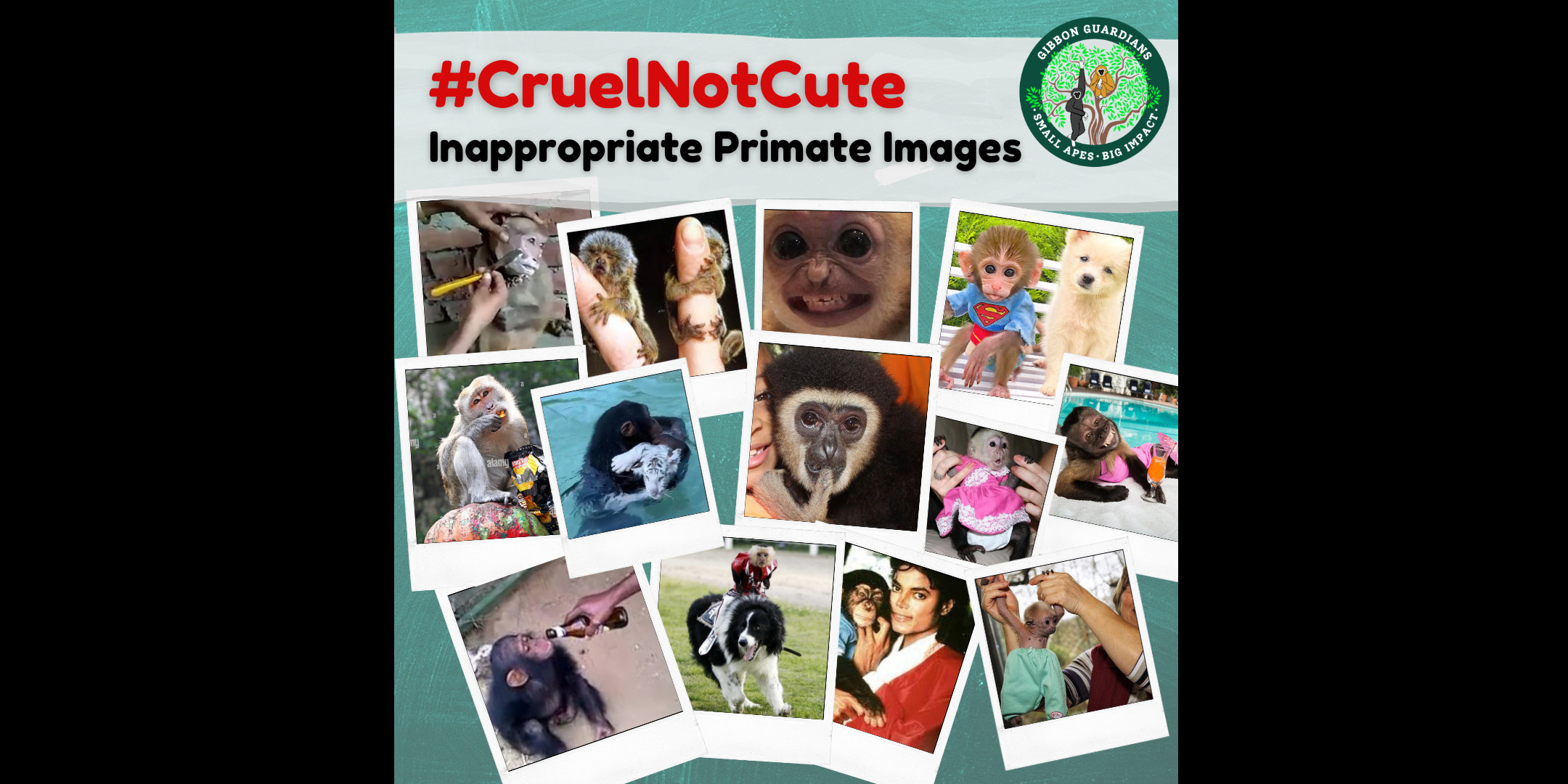

The Prime Earth Instagram account has multiple posts targeting these photos, a popular campaign entitled “Cruel Not Cute,” which includes explanations of the true repercussions of photos such as baby tigers cuddling up with humans or monkeys smiling with their teeth showing — harmless or even inspirational images to some (baby animals do look like they would be lovely to cuddle) but which have detrimental effects on the animals themselves.

Most of us have probably seen images of grinning primates on social media, sometimes even turned into memes. Memes are a form of communication, sometimes becoming a humorous shorthand for communicating an emotion or reaction. They’re embedded in internet culture — they are internet culture. However, there is a line between funny memes and perpetuating cruelty to animals. Dr. Jackie Prime, a primatologist and the founder and executive director of Prime Earth, believes that the line is very thin. Prime sees memes as a niche that may pave the way to normalizing and desensitizing animal cruelty.

The problem with these “funny” memes or images of primates in human habitats is that the images position the primates as happy, funny, or just adorable, while they are often, in fact, displaying fear-based behaviour or are in unnatural situations (for primates) that may quickly lead to aggression.

Prime and her team want to protect primates from these inappropriate and harmful situations by way of this new program. “Primate Protectors” trains citizens to identify and report these online images of primates; Prime Earth will also collect that data to inform and influence policymakers into taking stronger measures to protect primates. Brontë Slote is the advocacy team manager, leading a team of volunteers in the running of this project; reflecting the global nature of the program, Prime Earth’s volunteers are similarly located around the world.

While the internet has much to answer for, including the proliferation of images of primates in detrimental situations, it has also enabled organizations to engage people in their projects, creating citizen science projects like Primate Protectors, the Global Butterfly Census, and the Mapping Application for Penguin Populations and Projected Dynamics. NASA has a whole page of citizen science projects, including a number of their own; those who take part have the opportunity to both learn and contribute to disciplines that interest them.

I had the privilege of discussing Primate Protectors, the distortion of primate behaviour and even the blatant bullying of primates online with Slote and Dr. Prime.

The answers have been lightly edited for flow and clarity.

What inspired this mission?

One of our longest-running, most popular series on our Instagram (@gibbonguardians) is our “Cruel Not Cute” series, where we take examples of common images of primates, such as primates dressed in human clothes, smiling, or with their tongues hanging out, and explain that while these behaviours may seem cute, they are actually unnatural and representative of greater mistreatment behind the scenes. Our supporters quickly started finding examples of this harmful content across social media and took action commenting on the negative content and sharing it with us. However, engaging with content on social media (even in a negative way) is only registered as engagement and boosts it in the algorithms, increasing its profit for the creator and popularity across the platform. We needed a way to actually address this content, get it taken down, and create wide-scale changes in the types of primate content allowed on social media. From this, our Primate Protectors citizen science project was born.

Why is it important to protect the images of primates online?

Images and other social media content depicting primates online are only a snapshot into the realities of what life looks like for these individuals. This inappropriate content, which is often staged, does not tell us the full picture of what is happening behind the scenes. We can look out for signs that primates are in distress, like smiling, which is actually a fear grimace, or thumb-sucking, which is an expression of anxiety. So we know that something behind the scenes is wrong. But ultimately when the camera turns off, we don’t know the full extent of the harmful conditions or abuse these animals are experiencing. Primates are wild animals whose complex needs cannot be provided for in captivity, in particular situations of captivity where the primates are only seen as objects to be used for making money off of social media content.

Is there a blurry line between harmless fun and inappropriate images?

To the untrained eye, inappropriate images can easily be seen as cute and funny, however, once you know what to look for, it is easy to see a clear difference between examples of positive primate imagery and those that are harmful. For example, images of primates acting like humans (wearing clothes, eating human food, or performing human activities like riding a bike) may seem funny and cute at first, but these are completely unnatural behaviours and either harm the primate or are the result of abusive training practices. The only positive primate content is shared by reputable organizations, sanctuaries, and experts, who show primates engaged in natural behaviours, and any humans present are shown at a distance or are accredited experts supporting primate care and conservation.

In the age of people protesting against parks like Marineland, would photos like these further perpetuate an idea of animals performing?

Definitely! Content depicting primates for nothing but their entertainment value promotes the idea that all animals are objects for our entertainment. This normalizes performing animals and makes people not think twice about seeing animals in captivity and performing. Primate content on social media frames primates as “cute,” “fluffy,” and like “babies” to their human “parents.” This language combined with the prevalence of inappropriate images makes it seem like primates are good pets and that they are desirable to interact with at tourist attractions where people get to hold primates or take selfies with them.

Can you explain more about your data collection team? How does it work and who can join it?

We’re building a team of Primate Protectors around the world to identify harmful primate content on social media, report it, and track their data. It’s difficult to address inappropriate primate content online because it is nearly impossible to track where the content is being created to contact the relevant authorities in that area. The best way to combat this content is to report it on the social media platform that it is found on. This sends a clear message to social media corporations that this sort of harmful content is unacceptable and that users do not support it. However, a lot of platforms do not take primate mistreatment seriously, because they make the same common mistake to think these images are funny or cute. And that’s where our Primate Protectors come in. As well as reporting content on social media platforms, Primate Protectors are also part of our global citizen science data collection project, sharing the reports that they make with us. This data is then gathered together to get a complete picture of the issue of primate content and compile this information to influence policies and social media corporations to introduce large-scale changes and increase enforcement.

Do you have a specific goal you’d like to reach by the end of this mission?

Our Primate Protectors campaign is ongoing and we are looking forward to tracking the trends of primate content on social media over time and regularly compiling reports and updates to share with our supporters and partners. We hope that not only will this campaign generate the data needed to influence change in animal cruelty guidelines across major social media platforms, but also widespread awareness in society. When social media users recognize this content as harmful and stop engaging with it, content creators and social media platforms will have no choice but to address it. That’s one more positive step forward towards our mission at Prime Earth to create a more compassionate world.

How can people become a Primate Protector?

Anyone, aged 18 and up, can become a Primate Protector by signing up on our website (https://www.prime-earth.org/primate-protectors). To start contributing to data collection, all Primate Protectors must first complete our “Protector Check.” It’s a short test to make sure everyone is identifying content with accuracy by showing examples and asking people to identify the correct category that they fall into. Our team at Prime Earth supports Primate Protectors at every step along the way, from information on how to identify [inappropriate primate content] and step-by-step guides to reporting on different platforms, to wellness checks and compassion fatigue resources.

The first Primate Protectors have already begun collecting data, and anyone interested in joining in can register at any time. Dr. Prime notes that would-be Primate Protectors can review the materials on the Prime Earth website and take a practice “Protector Check” test to learn how to properly categorize the images. Upon registration, new Primate Protectors will receive a link to the real Protector Check, which can be taken whenever is convenient. Once the Protector Check test has been passed, it’s time to get started.

There are also weekly emails, quarterly newsletters, and occasional virtual webinars for those who want to dig a little deeper into the world of primates and how humans can help protect them. For more information, go to prime-earth.org or click here to go straight to the Primate Protector registration page.

Correction notice: this article has been corrected to reflect that Brontë Slote and Jackie Prime were involved in answering our questions (via email). Our apologies for any inconvenience caused.