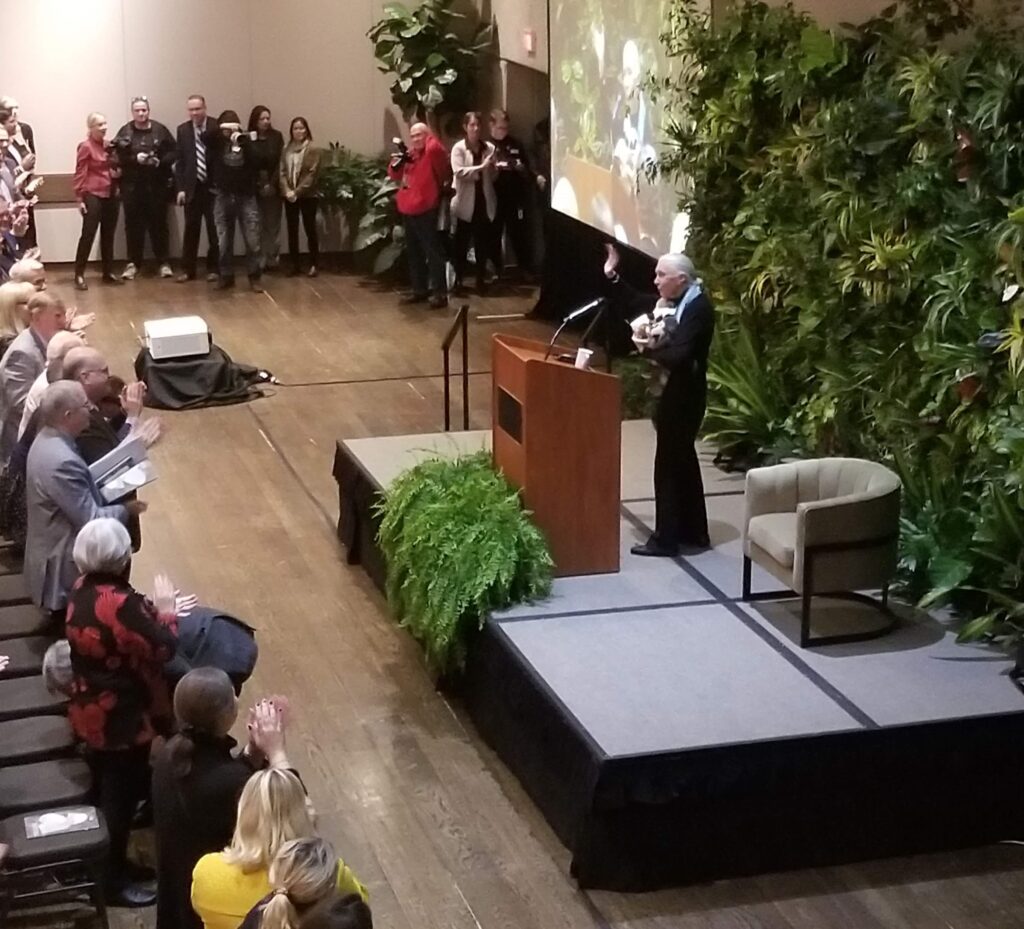

Two talks in one day at the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG): first 400 students in grades 4 to 6, then 400 adults (with a few children sprinkled throughout) not nine hours later, leaving both groups inspired to help change the world for the better. All in a day’s work for Dr. Jane Goodall, even at 89 years young.

Dr. Goodall has been breaking barriers of many kinds all her life. First, proving the naysayers wrong when they said a girl couldn’t go to Africa to study wildlife. Second, turning primatology —any discipline dealing with animal behaviour, really — upside down with her studies with chimpanzees demonstrating that our near cousins have compassion, feelings, kinship connections, that they use tools. All qualities that had been attributed only to humans previously. And then she skipped an undergraduate degree to go straight into a PhD program — at the University of Cambridge, no less.

Literal barriers were finally broken after nearly three decades of activism by Dr. Goodall and animal-rights groups on behalf of chimpanzees being held captive for research purposes in the United States; hundreds of chimps were moved to sanctuaries. And for years now, she has been travelling the world (63 countries so far), inspiring people to take care of our planet, using her vast and deep knowledge and love of animals to remind us that the differences between us and other species is much less than we like to think.

She reminds us that we are all connected: humans, other animals, plants, the environment. This fact underpinned both of Dr. Goodall’s talks at RBG yesterday.

During EcoFest, which began with Dr. Goodall’s talk to the students, and was followed by a pizza lunch and outdoor eco-activities with RBG staff, Dr. Goodall focused her message on the collective impact that children can have on the world. She has met groups of children working on local solutions for local problems through her Roots and Shoots program. Kids can become members online. Then, the idea is for them to go out in their own communities to identify problems and figure out what they can do to address them — a litter pick-up in their schoolyard or neighbourhood, or, like a group of Girl Guides in Manitoba, building birdhouses to give birds places to nest.

Each child can have a ripple effect: Dr. Goodall told the story of one of the first Roots and Shoots group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, who decided that they wanted to put trees back on a sacred hill, despite it being in an area of conflict over minerals. Their teacher went to much trouble to arrange for saplings, get the children to this hill, which was farther away than the children had realized, and negotiate the planting with the armed group in charge. Permission was granted, but the children had to be “accompanied by Congolese soldiers with AK-47s,” explained Dr. Goodall. Soon, one small girl was upset because she couldn’t dig into the hard ground, and one of the soldiers finally went to help her. Within 15 minutes, continued Dr. Goodall, “All of the soldiers had put down their guns to help the children plant their saplings.”

Just one example of that ripple effect at work. She gave more: Tanzanian children who worked to better the treatment of working donkeys; a child in Burundi pledging to get friends to each pick up 10 pieces of garbage each day.

More of Dr. Goodall’s incredible stories came out in the question-and-answer period. The classes in attendance had previously submitted questions for Dr. Goodall — excellent questions that brought out more pearls of wisdom, some of which she learned from her mother (“Work really hard…take advantage of every opportunity…and don’t give up!” and “Be absolutely passionate about whatever it is you decide to do.”)

Afterward, Jody Stein’s grade 5 class from Alton Village Public School stayed behind for a class photo with Dr. Goodall and presented her with a beautiful piece of art by Jake Soek, one of the students in the class.

Arhum Taufiq, another student from Alton Village P.S., said that the event was “very fun,” and that Dr. Goodall had inspired him to “stay off the electronics, stay off my phone and not just be swiping on it.” Andrew Wehbe’s favourite part was hearing of Dr. Goodall’s work with Gombe Stream National Park’s chimpanzees. What animal might he like to study? “Alligators,” was his swift reply. “I just like them and I know a lot about them.”

Given their rapt attention, it seems safe to say that all the students in attendance were listening carefully and inspired by Dr. Goodall.

The evening’s talk began with Dr. Goodall’s chimpanzee “pant hoot” call by way of introduction: “In chimpanzee language, ‘Me, Jane’.” When chimpanzee friends get separated, “as they sometimes do,” she explained, they do this call. When the other hears it, they “then reunite.” While the main message of the interconnectedness of all life on earth and the need to protect and conserve it necessarily stayed the same for the evening presentation, Dr. Goodall peppered this talk with asides that had the audience in stitches — and again, giving her their complete and earnest attention.

Dr. Goodall’s talk started from her childhood in southern England, where she was “born loving animals,” telling stories that demonstrated her sense of curiosity and exploration from a young age, all encouraged by her mother. “A different mother might have crushed that early curiosity,” she noted. Dr. Goodall took the audience with her from WWII England to Africa, post-secretarial school graduation, and into the office of paleoanthropologist and archaeologist Dr. Louis Leakey, who was sufficiently impressed with her knowledge of animals — and whose secretary had just quit — to ask her to come with him to Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. (This site later became well known for its stone tools made by human ancestors, and fossils of the hominins who made those tools, thanks to much work by Dr. Leakey and his wife, Mary Leakey.)

From Olduvai, Dr. Goodall went to Gombe and its chimpanzees, where she would experience “the best years of her life.” There, she made the ground-breaking discovery that chimpanzees made and used tools, and while it is now widely accepted that tool use is not just the domain of primates (crows, octopi, dolphins, and ants are amongst the other tool-using species), then, scientists thought that tool production and use were skills that only Homo sapiens had.

The chimpanzees eventually got used to Dr. Goodall, allowing her the opportunity to observe their emotions, personalities, and ties to each other, to see “how like us they are.”

She was moved to leave her fieldwork only in pursuit of activism, which led to the foundation of the Jane Goodall Institute. The Institute takes the approach of “community, then conservation,” working with local people to build up sustainable communities, and then, when the local people no longer need the bush meat trade to survive, for instance, can the work of helping the other animals happen.

Dr. Goodall ended the evening with a message of hope — with provisos and warnings. There is worry, of course, for the environment, loss of biodiversity, climate change: “Isn’t it bizarre that the most intelligent animal that’s ever walked the earth is destroying its only home?” But human intellect gives her hope, though we must come together to solve ecological problems, rather than working in silos. “We have to make sure we get together before its too late,” Dr. Goodall states. The passion, hard work and understanding of her Roots and Shoots children, many of whom are now adults and working to be part of the necessary solutions, give her hope. The indomitable human spirit gives her hope.

Both groups ended their inspiring sessions with a pledge, led by Dr. Goodall, of “Together we can! Together we will! Together we must! Change the world.”

We should all be inspired by Dr. Goodall to join her in this pledge — as the great scientist and conservationist herself says, “before the window is closed.”