By Leena Sharma Seth

April has been a busy month! It’s been feeling a little more like spring each day as the robins return, the flowers start to bloom, and the days get longer. This month also marks only the third time in a century that Sikhs and Hindus celebrated Vaisakhi/Baisakhi, Jews celebrate Passover, Muslims celebrate Ramadan and Christians celebrate Easter over an unusually holy weekend and month. So much love and joy to go around!

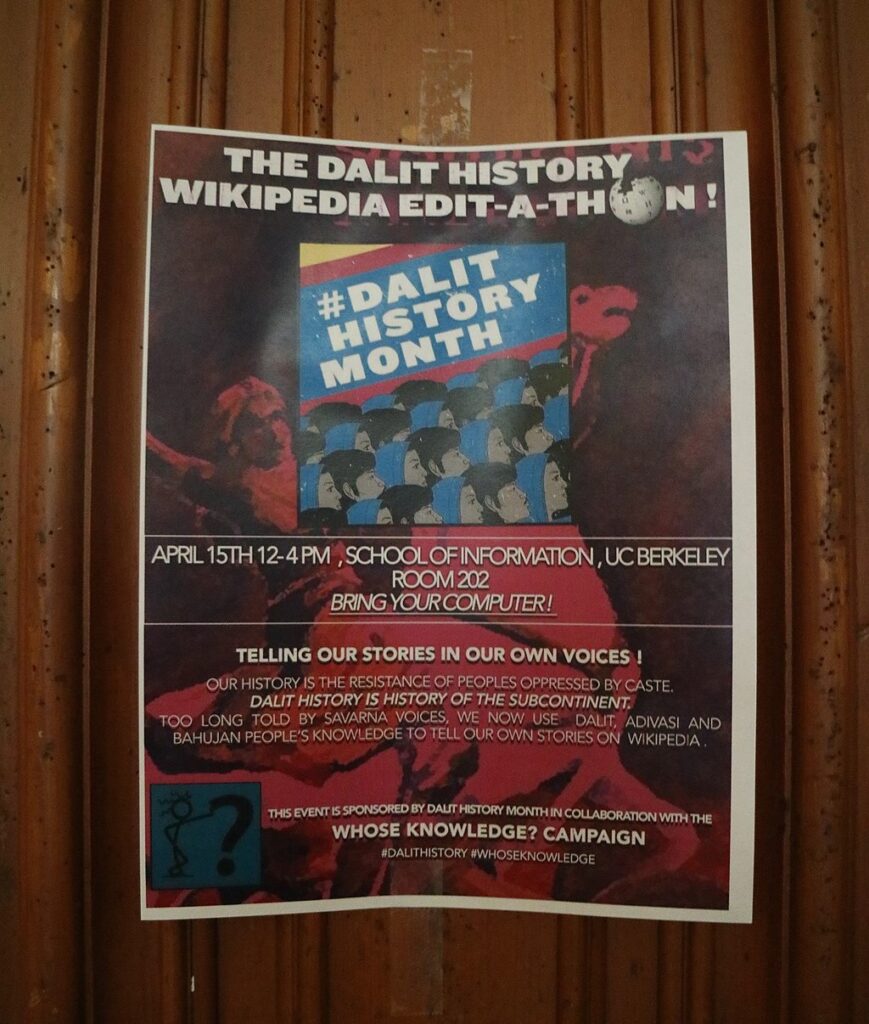

It really is an amazing time in global consciousness when every month of the year is an opportunity to learn about and celebrate the heritage, contributions, and excellence of different communities as well as to highlight the struggles, oppression, and discrimination of many of these communities who have been invisiblized (that is, intentionally made invisible) by mainstream media. This month marks Sikh Heritage Month, World Autism Month, and Dalit History Month, among others.

Along with many others who work in the equity, inclusion and belonging space, I dream of the day that dates and months like these no longer need to exist because we’ve achieved a state of true equity and inclusion for all members of the human family. However, until we’ve reached that place, I see these commemorations as opportunities to embody inclusion and belonging by learning more about each other’s stories, supporting liberation and the disruption of oppression where I can.

Dalit History Month may be the least well-known amongst these. Indeed, you may be wondering, what is a Dalit?

To answer this question, I’d like to briefly explain the caste system of India: “It is a social hierarchy passed down through families, a designation that cannot be changed, and it can dictate the professions a person can work in as well as aspects of their social lives, including whom they can marry. While the caste system originally was for Hindus, nearly all Indians today identify with a caste, regardless of their religion” (Sahgal et al., 2021).

As I understand it, the caste system is said to have been created from the body of Brahma, the Hindu god of creation. It essentially divides Hindus into rigid hierarchical groups based on their karma (action, from the notion of cause and effect) and dharma (living one’s life in accordance with their duty). There are four main castes or categories: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and the Shudras. Dalits were excluded from this system of Hinduism and were seen as forming a fifth caste, most commonly known as “untouchable.” Members of this caste were often relegated to the jobs that were “unclean” or “beneath” members of other castes, performing functions such as cleaning homes, streets, and other community duties. Dalits now profess various religious beliefs, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity, and Islam. Scheduled Castes is the official term for Dalits as per the Constitution of India.

Growing up in Canada as a child of Punjabi, Hindu, and Brahmin immigrants, my privilege as a Brahmin was largely invisible to me. For many years, I even told people that I was not a beneficiary of this system and that it was irrelevant to me. I heard family and community members say a lot of negative things about caste oppressed community members during my childhood, and remember hearing stories about the lengths my ancestors went to in order to “protect” themselves from becoming “impure” due to interactions with these caste-oppressed community members in India.

Dalit History Month was established in 2015 when Dalit activists Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Christina Dhanaraj, Maari Zwick-Maitreyi, Sanghapali Aruna, Asha Kowtal, and Manisha Devi, known as the Dalit History Month Collective, came together to advocate for April to become Dalit History Month. April was selected to honour Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar, known as the Father of the Indian Constitution and leader in the Dalit Liberation Movement, and Jyotirao Govindrao Phule, Indian social activist, businessman, and anti-caste social reformer, as both of their birthdays fell in April.

Dalit History Month has become an important month for me to learn and reflect on how I have personally benefited from the caste system. I’m early in my journey of reckoning with my complicity in this system of oppression, and a book that came out last year from Dalit-American feminist and founder of Equality Labs, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, called The Trauma of Caste, has been a powerful resource in my understanding of the caste system. Through learning, reflective writing, and with the fellowship of South Asian women-identifying community members (harm happens in community and so does healing), I am working to understand that caste is a dehumanizing and devastatingly harmful system of oppression, and also a system that my ancestors were beneficiaries of.

While the social and economic effects of the caste system are clear, here are some statistics that highlight the impact and harm from casteism to caste-oppressed communities in India:

- Over 40% greater infant mortality for Dalit and Adivasi (Indigenous) communities compared to 32% for the general Indian population (International Dalit Solidarity Network, 2015).

- Between 2015 and 2020, rape of Dalit women increased 45%, with an average of 10 Dalit women and girls being raped daily (Singh, 2022).

- Every 15 minutes, a crime is perpetrated against a Dalit (Soundararajan, 2022).

- The average age of death for a Dalit woman is 39 (Soundararajan, 2022).

The way I understand it now is that being Brahmin had something to do with how my family, my ancestors, survived the brutality of the colonization of India by the British, the partition of India (my father’s side of my family come from Sialkot, a part of India that became Pakistan), famine, etc. Being Brahmin not only gave us access to privileges, resources, pathways out of hardship that were not available to caste-oppressed and Adivasi peoples, but likely also gave my ancestors license to participate in and silently allow violence, dehumanization, and unspeakable atrocities against these communities. These are not easy truths to bear and I am learning to hold not only the intergenerational trauma my people endured from colonization, but also the weight of the harm and trauma that they inflicted on those who were vulnerable so that we could be secure.

It’s my responsibility to continue to learn my history and to learn about the ways my family benefited, how I still benefit, so that I can truly work to use my power, privilege, and platform to advocate for change.

Canada has made some significant strides in advancing awareness of caste oppression as well as greater protections for those harmed by the impact of casteism and hate that comes from those who are casteist:

- Last year, British Columbia became the first province to officially declare April as Dalit History Month.

- This year the City of Burnaby, B.C., declared April 14 as the Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Day of Equality.

- Last month (March), the Toronto District School Board, the largest school board in Canada, was the first school board in Canada to pass a motion to recognize caste-based discrimination.

Though we still have a lot of work to do, I’m really encouraged by outcomes like this and will continue to spend the month unlearning and learning. Hope is a powerful engine for change. I leave you with a quote from someone I deeply admire and respect, Thenmozhi Soundararajan:

“I am a daughter of a people who have been oppressed for thousands of years, I am also the artifact of centuries of their love and resilience. In that there is a hope for everything. May a thousand flowers bloom in your heart and in mine for our liberation.”

Leena Sharma Seth (she/her) is a settler and award-winning consultant, coach, trainer, and speaker at a firm she founded called Mending the Chasm. She works with businesses, organizations, and communities who are ready to create communities and workplaces that are inclusive, belonging-abundant, and safe for all members. When she’s not kicking at the darkness until it bleeds daylight, she’s enjoying road trips, 80s Bollywood music, and perfecting the art of baking cinnamon buns. She’s proud to call Burlington home and to be raising her children with her partner Sanjay.

Sources:

International Dalit Solidarity Network. 2015. India’s health inequality severely affects Dalits. Url: https://idsn.org/indias-health-inequality-severely-affects-dalits/ (accessed April 25, 2023).

Sahgal, N., Evans, J., Salazar, A.M., Starr, K.J., and Corichi, M. 2021. 4. Attitudes about caste. Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation. Pew Research Center. Url: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/06/29/attitudes-about-caste/ (accessed April 25, 2023).

Singh, A. 2022. India: why justice eludes many Dalit survivors of sexual violence. Al Jazeera. Url: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/8/india-why-justice-eludes-many-dalit-survivors-of-sexual-violence (accessed April 25, 2023).

Soundararajan, T. 2022. The Trauma of Caste. North Atlantic Books.